Bed Bugs Biology and Behavior

ID

ENTO-8P

EXPERT REVIEWED

Introduction to the Bed bug Lifecycle

The bed bug species that is infesting homes today are the descendants of cave dwelling bugs that originally fed on bat blood. When humans began living in the caves (100,000 to 35,000 years ago, depending on the source), the bugs began feeding on humans. Later, when humans moved out of the caves and started their agricultural civilizations, the bugs moved with them. Since that time, humans have carried bed bugs all over the world.

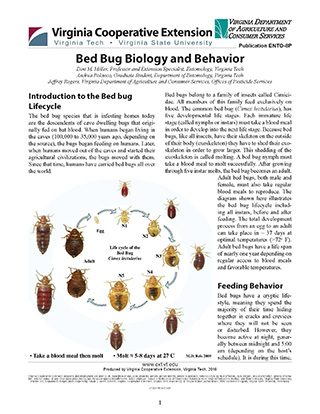

Bed bugs belong to a family of insects called Cimicidae. All members of this family feed exclusively on blood. The common bed bug (Cimex lectularius), has five developmental life stages. Each immature life stage (called nymphs or instars) must take a blood meal in order to develop into the next life stage. Because bed bugs, like all insects, have their skeleton on the outside of their body (exoskeleton) they have to shed their exoskeleton in order to grow larger. This shedding of the exoskeleton is called molting. A bed bug nymph must take a blood meal to molt successfully. After growing through five instar molts, the bed bug becomes an adult. Adult bed bugs, both male and female, must also take regular blood meals to reproduce. The diagram shown here illustrates the bed bug lifecycle including all instars, before and after feeding. The total development process from an egg to an adult can take place in ~ 37 days at optimal temperatures (>72o F). Adult bed bugs have a life span of nearly one year depending on regular access to blood meals and favorable temperatures.

Feeding Behavior

Bed bugs have a cryptic lifestyle, meaning they spend the majority of their time hiding together in cracks and crevices where they will not be seen or disturbed. However, they become active at night, generally between midnight and 5:00 am (depending on the host’s schedule). It is during this time, when the human host is typically in their deepest sleep, that bed bugs like to feed.

Bed bugs are known to travel many yards to reach their human host. Bed bugs are attracted to the CO2 produced by the host’s exhalations. The increase of CO2 in the room stimulates hungry bed bugs to begin searching. They cannot tell where the host is but they know one is present. Bed bugs are also attracted to body heat, however, they are only able to detect heat from distances less than 3 feet. It is not well understood how bed bugs hiding in a closet are able to find a host located in a bed across the room. However, bed bugs are able to move very quickly, and it is thought that they do a lot of wandering around before they are able to locate their food. Ideally, most bed bugs would like to aggregate near the host’s bed, on the mattress or in the boxsprings, when they are not feeding. However, this is not always possible in heavy infestations where bed bugs are crowded and many bed bugs have to seek refuge at distances several yards from the host.

Once a bed bug finds the host, they probe the skin with their mouthparts to find a capillary space that allows the blood to flow rapidly into their bodies. A bed bug may probe the skin several times before it starts to feed. This probing will result in the host receiving several “bites” from the same bug. Once the bed bug settles on a location, it will feed for 5-10 minutes. After the bed bug is full, it will leave the host and return to a crack or crevice, typically where other bed bugs are aggregating. The bed bug will then begin digesting and excreting their meal. Bed bugs typically feed every 3-7 days (although some may feed more often). Thus on any particular day, the majority of the population is not feeding but in a digesting state.

Mating Behavior

After feeding, adult bed bugs, particularly the males, are very interested in mating. Cimicid bugs have unique method of mating called “traumatic insemination”. This mating behavior is considered “traumatic” because the male, instead of inserting his reproductive organ (paramere) into the female genitalia, he literally stabs it through her body wall into a specialized organ on her right side, called the Organ of Berlese. The male sperm is released into the female’s body cavity, where over the next several hours it will migrate to her ovaries to fertilize her eggs.

The stabbing of traumatic insemination creates a wound in the female’s body that leaves a scar. The female’s body must heal from this wound and consequently, females are known to leave aggregations after being mated several times to avoid any further abuse. Studies have shown that the process of healing from traumatic insemination has a significant impact on the female’s ability to produce eggs. In fact, females that mate only once, and are not subjected to repeated stabbings by the male will produce 25% more eggs than females that are mated repeatedly.

In practical terms, this means that a single mated female brought into a home can cause an infestation without having a male present, as long as she has access to regular blood meals. The female will eventually run out of sperm, and will have to mate again to fertilize her eggs. However, she can easily mate with her own offspring after they become adults to continue the infestation.

Egg Production:

The number of egg batches a female will produce in her lifetime is dependent on her access to regular blood meals. The more meals the female can take, the greater the number of eggs she will produce. For example, the average adult female will live about one year. If she is able to feed every week, she will produce many more eggs in that year than if she is only able to feed once a month.

On average:

- A female bed bug will produce between 1-7 eggs per day for ~10 days after a single blood meal. She will then have to feed again to produce more eggs.

- A female can produce between 5 and 20 eggs from a single blood meal.

- The number of male and female eggs produced is about the same (1:1 ratio).

- A single female can produce ~ 140 eggs in her lifetime.

- Eggs can be laid singly or in groups. A wandering female can lay an egg anywhere in a room.

- Under optimal conditions, egg mortality is low and approximately 97% of the bed bug eggs hatch successfully.

- At room temperature (>70o F), 60% of the eggs will hatch when they are 6 days old; >90% will have hatched by the time they are 9 days old.

- Egg hatch time can be prolonged by several days by lowering ambient temperature (to 50o F).

- Due to the large numbers of eggs a female can produce under optimal conditions (at temperatures >70o F but < 90o F, and in the presence of a host), a bed bug population can double every 16 days.

Nymph Development Time

The time it takes any particular bed bug nymph to develop depends on the ambient temperature and the presence of a host. Under favorable conditions, such as a typical indoor room temperature (>70o F), most nymphs will develop to the next instar within 5 days of taking a blood meal. If the newly molted instar is able to take a blood meal within the first 24 hours of molting it will remain in that instar for 5-8 days before molting again. At lower temperatures (50o F - 60o F), a particular instar may take two or three days longer to molt to the next life stage than a nymph living at room temperature. However, if a bed bug nymph does not have access to a host, it will stay in that current instar until it is able to find a blood meal, or it dies. The time for a bed bug to develop from an egg, through all five nymphal instars, and into a reproductive adult is approximately 37 days.

Even under the best conditions some bed bug nymphs will die prior to becoming adults. The first instars are particularly vulnerable. Newly hatched nymphs are exceptionally tiny and cannot travel great distances to locate a host. If an egg is laid too far from a host, the first instar may die of dehydration before ever taking their first blood meal. However, laboratory studies have found that overall bed bug survivorship is good under favorable conditions, and that more than 80% of all eggs survive to become reproductive adults.

Adult Bed Bug Life Span

The most recent studies indicate that a well-fed adult bed bug held at room temperature (>70° F), will live between 99 and 300 days in the laboratory. Unfortunately, we do not know exactly how long a bed bug might live in someone’s home or apartment. No doubt it will be at least several months but conditions are usually more challenging for the bed bugs living in human dwellings than they are in the laboratory (it is hard to find food, there are fluctuations in temperature and humidity, insecticides may be present, it is easy to get crushed etc.) and these conditions will have a negative impact on bed bug survival.

A recent laboratory study has shown that starvation can greatly reduce bed bug survival. This modern study contradicts European studies conducted in the 1930s and 40s which stated that bed bugs could survive periods of starvation lasting more than one year. While this may have been true for individual bed bugs in the UK living at very low temperatures (< 40° F; because of no central heating); modern bed bugs collected from homes in the United States do not live that long. On average, starved bed bugs (at any life stage) held at room temperature will die within 70 days. Most likely these bed bugs are dying of dehydration, rather than starving to death. Because bed bugs have no source of hydration other than their blood meal, dehydration is the greatest natural threat to their survival while living in the indoor environment. In fact, one of the reasons that bed bugs pack themselves so tightly into small cracks and crevices is so that they can maintain a microhabitat of favorable temperature and humidity, thus increasing their ability to survive periods of starvation.

Bed Bugs that are Resistant to Insecticides

The lifecycle data presented in this publication is based on research conducted using bed bugs collected from apartments within the state of Virginia. These populations have documented resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. Laboratory studies have indicated that resistant bed bugs have a shorter developmental time (several days), shorter life spans and lower levels of egg production than bed bugs that are not resistant to insecticides. At the time of this writing, practically all “natural” bed bug populations collected in Virginia have been found to be a least somewhat resistant to pyrethroid insecticides.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

August 2, 2024