Teaching Tips and Techniques: A Dialogue Learning Approach

ID

FST-284NP (FST-452NP)

Volunteer teachers are important to Virginia Cooperative Extension (VCE). Volunteers convey information on a variety of topics by teaching or assisting with programs. Although there are many methods for delivering content, this publication will focus on a selection of teaching techniques to foster dialogue.

Most educators are probably familiar with the more traditional “telling approach” to teaching because that is how most received their education. The “telling approach” is a traditional student and teacher relationship where the teacher stands in front of the class and lectures to the students. However, a dialogue learning approach involves a conversation between the educator and learners. This approach may make the learning experience more meaningful to the learner and allows them the time to build confidence so that they may apply any new without supervision (Norris 2003). In dialogue, learners make meaning of the information and decide what they will do with it instead of being “told” what to do.

Flipped Classroom

Using a “flipped classroom” approach can help you focus the in-person program time on learner- centered dialogue while also giving learners the opportunity to access the content that is important to the subject at hand. In this approach, learners are provided with content such as readings, videos, or recorded lectures to review on their own before the in-person class time. In class, rather than delivering a lecture, the facilitator uses active learning methods to engage the learners in discussing the content and applying it through activities and problem-solving (Herreid and Schiller 2013). This methodology shifts programming from a focus on telling information to learners to a focus on engaging learners in actually making meaning of and using information (Strong, et al. 2015).

Preparing to Learn

Create a positive learning environment from the first encounter. Some suggestions to set the tone for a program and create a positive environment include the following:

Make welcome signs and place them where everyone will see them

Greet learners warmly as they arrive

Have music on in the background while welcoming learners. Be mindful not to make the music too loud so as to not distract or make it difficult to hear each other, and turn off the music when the program begins

Provide name tags and ask learners to write their names in large print

Use people’s names immediately

Arrange tables or chairs to enhance dialogue

Have a decorative table with handouts and props related to the subject matter that the participants can see and touch

Ensure the workspace is ready when learners arrive

Welcoming Learners

Introduce yourself and the program you are representing. Provide learners with an overview of your agenda, including objectives of your lesson plan; what you hope to get out of the class; and the length of your program.

Describe the program. Give learners an idea of what you will need from them. For example, “Today I will ask you to participate in a 20-minute lesson, then we will practice what we have learned through a shared activity” You are defining your expectations up front so the learners will not need to guess the agenda.

Offer a voice by choice. Being called on and being made to speak in front of an audience is terrifying for some people. One of the best things you can offer your learners is letting them know up front that you will not call on anyone or go around the room for responses. If you break this rule, you will lose their trust (Norris 2003, 2008).

Five Facilitation Principles

The following are five learning principles that will help you facilitate dialogue learning with your audiences.

Respect. Respect who they are, where they have been, and what they know. Remember, adults have many life experiences that they bring with them to your program.

Safety. Learners should feel free to participate fully without fear. Offer gratitude when a learner shares an idea.

Inclusion. Everyone is equal and should be made to feel part of the group.

Engagement. Learners should be given the opportunity to practice or apply with the material rather than just sitting and listening.

Relevance. Find out why the information you are presenting is important to your learners and how it has personal meaning to them (Norris 2003, 2008).

The Power of Open Questions

Open questions focus on asking questions that encourage a more reflective response and not just “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know.” Open questions encourage a conversation between the presenter and the audience. Developing these types of questions may require some planning, so you may find it helpful to write them down. Over time as you become more comfortable with asking open questions, you should be able to do so without as much planning beforehand.

Open questions have no correct answer and invite the participant to dig a little deeper into their own experiences. These questions also give learners a chance to show you what they know and who they are (Norris 2003, 2008).

Some examples of open questions include the following:

Why do you think this might be? (e.g., Why do you think streams in urbanized areas might be warmer than in more forested areas?)

Can you describe an experience you have had that relates to this question/topic/example?

What have been some of your experiences with? (fill in the blank with the concept or topic of discussion)

How do you see (fill in the blank with the topic or concept of discussion) making a positive difference?

Based on what we have discussed up to this point, what is leaving you curious?

Participant Involvement

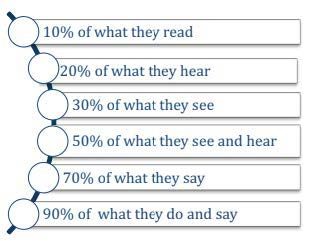

People remember new information when they do something and talk about it. According to Magnesen (1983), adults will generally remember:

Ways to Increase Participation

Creating opportunities for participants to interact is a common approach for increasing participation, can help start a conversation, and help learners make meaning of their experience (Norris 2003, 2008).

One way to facilitate partnering interactions during your workshop or lesson is by utilizing open questions. Partnering interactions allow learners to answer an open question as part of a duo or smaller group (up to 4 people). This smaller group helps learners to feel safe in responding without having to do so in front of the entire group. The small group can report answers back to the entire group as they choose. Again, this is an example of “voice by choice.”

Some examples of partner interactions include:

- Walk-and-talks, where partners walk while they are discussing the topic, can be effective because it gets people up out of chairs and moving around. It is helpful to structure the interaction as think-pair-share, meaning that each participant has time to quietly reflect on the question at hand and jot down their own ideas before starting to discuss them with a partner/group, then the pairs/groups discuss the question, and after there is an opportunity for them to share key ideas with the larger group. Make sure to limit the time for discussion so that learners do not become bored and get off topic. These can be most appropriate with groups of two or three people.

- Creating groups of three people can be helpful when you are teaching a specific skill. The third person can serve as an observer of their partners as they practice the skill.

Table chats can include up to four people and are useful if your tables are round and small enough for everyone to participate. Table chats still include a short discussion of the specific topic and work well if the group is developing a chart, a checklist, or completing another task as part of the discussion.

The 4 As

Now that we have discussed how to increase participation and facilitate dialogue, let’s look at four specific activities – Anchor, Add, Apply, and Away – to help make your program interactive and informative. These activities are especially effective if you are seeing learners more than one time (Norris 2008).

ANCHOR activities connect the topic to the learners’ lives and serve. They also set the tone of your program and get learners ready for learning.

ADD activities provide new information (this is the information that is the objective of your presentation). Share your lesson or program objectives here. Select three of your most important messages.

APPLY activities give learners an opportunity to practice using the information that you presented in the session. This is where your learners will do something with the content or skill they just learned. It can be as simple as a partner interaction or more complex such as producing something.

AWAY activities encourage learners to take the new information with them when they leave your session and apply it to their own lives. This provides a conclusion to your program. Review the content that was previously covered and ask them to summarize what they have learned. Ask learners to share one thing they will do as a result of today’s class. When you meet again, discuss how learners did on their goals. If they did not reach their goals, consider another approach that is more doable. The focus can be on what barriers they need to deal with in overcoming their challenges.

Remember to use open-ended questions, for example:

What are your questions?

Based on what we have discussed today, what more do you want to know or learn?

In what way has our discussion sparked your curiosity? (Norris 2003, 2008).

Ideally, learners should experience all four As. Depending on the type of learning experience, you may only incorporate a few of them. Regardless of how many of these activities you use, the learners need to be able to apply what they have learned (Norris 2003, 2008).

Elements of Waiting

As you ask open questions, give learners time to think about the question, choose their response, and feel comfortable in sharing. You might try counting (in your head) to 5 or 10. Even if this feels uncomfortable to you, the benefits will not be lost on the participant. You will demonstrate your genuine curiosity in what they have to say. If you do not wait for them, you send the signal that what they had to say was not that important, and it will be harder to get them to participate in the program. Do not fear or avoid long pauses or silence; embrace it and learn to be comfortable with discomfort (Norris 2003, 2008).

It is likely that someone will speak by the time five seconds are up. If not, do not break the trust factor and call on someone to speak. Feel free to offer some suggestions or move on. Have a back-up activity ready to generate discussion on the topic if you are not getting a response from the group.

A Few Additional Things to Remember About Adult Learners

Dialogue learning always relies on understanding specific characteristics about adult learners.

According to Daugherty (2017a; 2017b), the following are some specific characteristics to keep in mind as you implement the teaching techniques outlined in this document.

Adult learners are autonomous and self-directed. This means that you need to actively involve them as learners. Try to find out what learners want to learn before designing your session or program. You can teach best by facilitating.

Adult learners have a foundation of knowledge and life experiences. Acknowledge the expertise of learners. Encourage learners to share experiences and knowledge.

Adults are goal-oriented. Adults have clear objectives. Have a clearly defined plan for your program and one or two simple objectives. If you appear to be disorganized, people will feel like they are wasting their time.

Adult learners are relevancy-oriented. Activities and topics should be relevant to the defined objectives, and thus relevant to the learner.

Adult learners are practical. Explicitly state how the content applies to learners’ lives.

Adult learners need to be respected. Treat learners as equals. Acknowledge the wealth of knowledge learners bring to your program.

Working with Youth

Youth, like adults, learn best when they have an opportunity to do what it is they are learning. 4-H prides itself on teaching youth through hands-on activities. Remember, just like adults, youth want to be active; they do not want to sit and listen to someone lecture. This is especially true in after- school settings where children have been sitting all day; they do not want to come to a nutrition or gardening lesson and sit and listen to someone talk. Make sure you plan lots of activities to get youth up and moving around. Your local Extension Agent for 4-H Youth Development can also train you on how to work with youth in your programs. Contact your supervising Extension Agent for more information.

Steps to Plan a Learner- Centered Program

As you consider a more learner-centered approach to your programs, there are multiple methods for preparation. However, the following seven steps are helpful in developing an entire program (Vella 2000, 2002).

In this publication, these seven planning steps will be briefly described to help you get started.

However, it is important that you work with your supervising Extension Agent to complete these steps. If you work with other Extension programs, you may contact other Extension professionals who are experienced in working with this style of program planning:

- Who: Describe your learners. How many learners are you planning to attend? What is their previous experience? Where are they coming from? Who is leading or co-leading the program?

- Why: What do the learners need and want? Why is this program needed for the learners?

- When: Specify the date and time of your program. What is the duration of the program?

- Where: List the location where you will hold your program. What materials and equipment are already available at the location? What will you need to provide?

- What: Develop the content for the program. What do learners need to know related to this lesson or program? How will they best learn it? (Norris 2003). This step can take some extra time to develop, especially as you consider how (and in which order) you will deliver the content. Also, consider how much time you will have to cover the content. Do you need to pare down or increase the content to fit within the time frame of your program? Your supervising Extension Agent or professional can assist you. with this step.

- What for: Describe what your learners need to be able to do or to accomplish as a result of learning the content. According to Vella (2000, 2002), this step will include developing some achievement objectives. Work with your supervising Agent or Extension professional to develop these objectives.

- How: Create learning tasks to ensure the achievement objectives are met. This step gives learners the opportunity to think about the content and consider how they will use it in the future. These learning tasks should be based in the Four A’s Model: Anchor, Add, Apply, and Away (Norris 2003) mentioned previously.

Work with your supervising Extension Agent or other Extension professional to develop these learning tasks. As you plan your program using these seven steps, consider putting them into a blank chart with two columns. The left column should list the seven steps, and the second column describes each step. Use blank poster paper to write out this seven-step plan (Norris 2003, 2008).

In summary, planning programs and incorporating learner-centered dialogue can take some time as you work in partnership with your supervising Extension Agent or other Extension professional. However, it is well worth the effort to make sure your learners can actively practice what they have learned and make it more applicable to their lives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Davis, Jennifer Abel, Lynn Margheim, and Melissa Chase for their efforts on previous versions of this publication.

References

Daugherty, R. 2017a. “The Volunteer Teacher Series: The Effective Volunteer Teacher.” Fact Sheet T-8201, Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Service. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/the- volunteer-teacher-series-the-effective-volunteer-teacher.html

Daugherty, R. 2017b. “The Volunteer Teacher Series: Teaching Adults.” Fact Sheet T-8202, Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Service. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/the-volunteer-teacher-series-teaching-adults.html

Herreid, C. F., & Schiller, N. A. 2013. Case Studies and the Flipped Classroom. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(5), 62–66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43631584

Magnesen, V. 1983. Innovative Abstracts 5:25. National Institute for Staff Organizational Development. University of Texas, Austin.

Norris, J. A. 2003. From Telling to Teaching: A Dialogue Approach to Adult Learning. Myrtle Beach, SC: Learning by Dialogue.

Norris, J. A. 2008. Ya Gotta Have Heart! Myrtle Beach, SC: Learning by Dialogue.

Strong, E., Rowntree, J., Thurlow, K., & Raven,

M.R. 2015. The case for a paradigm shift in extension from information-centric to community-centric programming. Journal of Extension, 53(4).

Vella, J. 2000. Taking Learning to Task. Jossey- Bass. San Francisco, CA.

Vella, J. 2002. Learning to listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. San Francisco, CA.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

July 17, 2023