Facilitating Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems

ID

SPES-144NP

Contents

Why Community, Local, and Regional?

VCE Model of Community, Local, Regional Food System

How does your community get started?

Step 1: Invite a few people to join you

Step 2: Engage a diverse group of people in the discussion

Step 3: Meet with the Steering Committee

Step 4: Communicate with group members

Step 5: Gather relevant facts and trends

Step 6: Understand the Theory of Change

Step 7: Describe the group’s preferred future

Step 8: Explore and expose the options and select the focus

Step 9: Build a community food system strategic plan

Step 10: Write the plan of work

Step 11: Moving Forward with Continued Networking

Appendix A: The Seven-Community Capitals

Appendix B: Community Capital Stakeholder Identification Worksheet

Appendix C: Steering Committee & Community Discussion

Appendix D: Steps of the Logic Model and Action Plan Templates

What is a food system?

“Food is the connector of all.”

A food system describes all the components including production, processing, distribution, sales, purchasing, preparation, consumption, and waste disposal pathways. According to the American Planning Association (Hodgson, 2011), a healthy, sustainable food system is:

- Health Promoting. Supports the physical and mental health of all farmers, workers, and eaters. Accounts for the public health impacts across the entire lifecycle of how food is produced, transformed, distributed, marketed, consumed, and disposed.

- Sustainable. Conserves, protects, and regenerates natural resources, landscapes, and biodiversity. Meets our current food and nutrition needs without compromising the ability of the system to meet the needs of future generations.

- Resilient. Thrives in the face of challenges, such as climate change and its effect on food production, increased pest resistance, and declining, increasingly expensive water and energy supplies.

- Diverse in Size and Scale — Includes a diverse range of food production, transformation, distribution, marketing, consumption, and disposal practices, occurring at diverse scales, from local and regional to national and global. Geography — Considers geographic differences in natural resources, climate, customs, and heritage. Culture — Appreciates and supports a diversity of cultures, socio-demographics, and lifestyles. Choice — Provides a variety of health-promoting food choices for all.

- Fair. Supports fair and just communities and conditions for all farmers, workers, and eaters. Provides equitable physical access to affordable food that is health promoting and culturally appropriate.

- Economically Balanced. Provides economic opportunities that are balanced across geographic regions of the country and at different scales of activity, from local to global, for a diverse range of food system stakeholders. Affords farmers and workers in all sectors of the system a living wage.

- Transparent. Provides opportunities for farmers, workers, and eaters to gain the knowledge necessary to understand how food is produced, transformed, distributed, marketed, consumed, and disposed. Empowers farmers, workers, and eaters to actively participate in decision making in all sectors of the system.

Why Community, Local, and Regional?

You might wonder why the descriptors ‘community, local, and regional’ precede the words food system. Let’s start with community and why it is an important descriptor and part of the food system. The food system that makes food available and accessible is an important component of community economic development and indicator of social well-being within a community and region. Yet, food and the food system is often overlooked as a connector and undervalued as a means and strategy for building health, wealth, connection and capacity where food is produced and most needed (Meter, 2011). At the same time, U.S. families and households spend over $1.46 trillion on food each year. In 2014, food purchases were the third largest household expenditure after housing and transportation. Hence, the potential for impact and change at a community level is significant.

A community-focused food system is a collaborative network that integrates and encourages sustainable food production, processing, distribution, consumption and waste management in order to enhance the environmental, economic and social health of a particular place. The work entails being civic-minded and being vested in the well-being of everyone in the community. Therefore, a community-focused food system must be cultivated and nurtured by local leadership engaging farmers, consumers and communities to create a more resilient locallybased, self-reliant food system, and economy.

Through the years, the words ‘local’ and ‘regional’ have been used as descriptors of food miles, geographic proximity, product identity, and a sense of place such as a specific county, multicounty area, or known region. Additionally, the words have been used to encourage deeper, more transparent conversations from field to fork to help consumers know where their food comes from and for farmers to better tell their stories.

From an economic development perspective, the emphasis on community, local, and regional is a nested approach to development. The approach seeks to strategically benefit neighborhoods, towns, cities, and counties at a granular level from the ground up. The development precept and understanding is that if local towns, cities, and counties are vibrant and strong socially, economically, and environmentally, the impact and effects of community and local food system development will be noticeable at the regional and state levels as well.

Why is this work important?

Since everyone needs to eat each day to thrive, the food system affects and touches everyone on a daily basis. Therefore, the local and regional food system is an important resource and consideration for long-term community economic development, well-being, self-reliance, emergency preparedness, and democracy.

When the food system is considered more comprehensively and holistically, its relationship to community health, wealth, connections and capacity and other elements of overall community well-being becomes more apparent. Because a food system is so closely interconnected to production, processing, distribution, sales, purchasing, preparation, consumption, and waste disposal pathways of food, its significance to individuals, communities, and nations cannot be overstated.

There is unprecedented public interest in local food, knowing where food comes from, and how food is produced. A local food system allows consumers to know the farmer, strengthen and connect to locally owned businesses and farms that provide essential human needs to a region. A regional food system can address issues of seasonality and logistical efficiency, while cultivating local farming and business leadership. An economically embedded and communitybased regional food system can preserve local and regional identity, and benefit the long-term social and economic health and viability of communities.

Community conversations about food, size, scale, geography, culture, and choice can lead to deeper discussion about the values a community holds and the vision people have for the present and future. AbiNader et al. (2009) developed a shared-value framework based on Whole Measures of CommunityBased Food Systems to include measures for: Healthy People, Food Security, Sustainable Farmland and Natural Resources, Agricultural Profitability, Thriving Economies, Justice and Fairness, Safe and Nutritious Food and Water, and Viable Communities.

Virginia Cooperative Extension uses the sharedvalue and whole measures framework as a model to guide its work and the processes to support the development of community, local, and regional food systems. (Niewolny et al., 2016)

How does your community get started?

Your community members are wondering why they do not have access to home-grown produce and meat products and considering the possibility of growing vegetable gardens. Farmers are searching for new markets for their crops and products. Residents are struggling with health issues impacted by inappropriate diets. Questions are being asked about recycling, composting, and waste management.

Throughout the community, people are questioning the conditions and practices that are directly related to a community food system (CFS). The topics might include:

— Community gardens, farmers markets

— Community Support Agriculture (CSA)

— Conservation agriculture

— Consumer food preparation and preservation

— Models of food distribution and aggregation (e.g., food hubs)

— Food processing and safety

— Food justice and food sovereignty

— Food security (household and community)

— Food and agriculture policy

— Innovation in educational approaches, processes, and evaluation

— Institutional food procurement and preparation (e.g., farm-to-school, farm-to-university, and farm-to-hospital)

— Marketing and markets

— Nutrition education and health promotion

— Supporting producers/growers with startup and sustainability

— Resource and waste recovery

— Urban agriculture

When people are asking questions and wondering about possibilities, it is time to bring these individuals to the table for a conversation.

Sometimes, it is just a couple of innovative thinkers who have a clear vision of what might be possible in their communities. If so, start with these few people and use your expertise to guide them through a process that is inclusive and leads to action.

Step 1: Invite a few people to join you for coffee or lunch.

This friendly gathering will be the first time the thought of exploring and building a thriving community food system will be discussed.

- Ask the group about their own experiences with local food availability.

- Explore areas of your community where residents have difficulty purchasing produce, meats, and other farm products.

- Share facts you have gathered on your community’s food access and equity issues.

- Identify whether or not these issues should be part of a broader conversation that would lead to a positive change in the community food system.

You have had the first conversation and your group agrees that the community is ready for a change in the current conditions and practices. You are now ready for Step 2!

Step 2: Engage a diverse group of people in this discussion by creating a CFS steering committee.

- Bring the original group together for another conversation. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency published Local Foods, Local Places Toolkit which provides guidance for selecting participants. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-10/documents/lflp_toolkit_508-compliant.pdf

- Identify a wide-ranging and diverse listing of possible Steering Committee members. If you already have a community food policy council or food coalition, use this group or a few group representatives as your starting point. Then recruit additional people who may have never thought about community food systems (by that terminology) or who have realized they have a stake in this work.

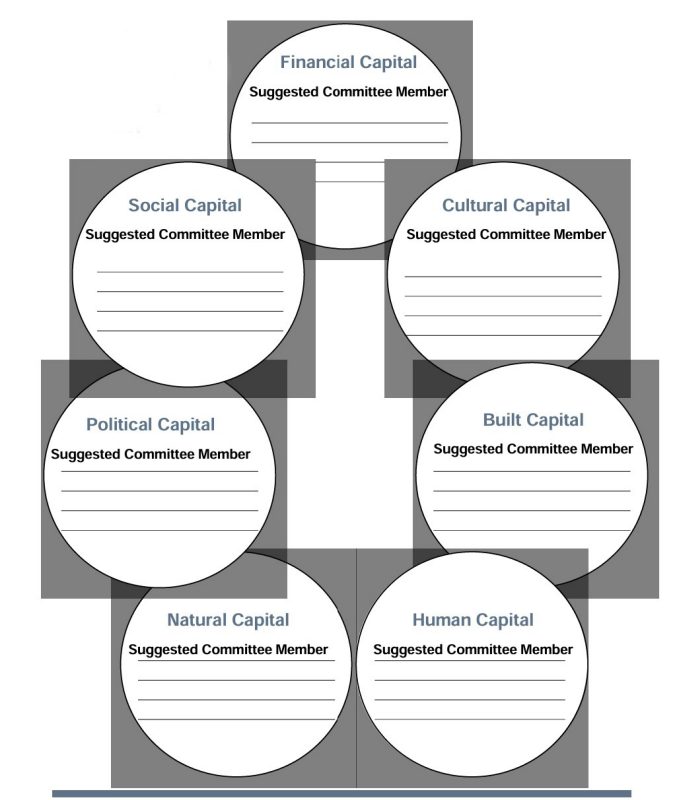

How do you know who to include? Consider using the Seven Community Capitals developed by Emery and Flora (2006) as a starting point (Appendix A). The capitals are categories that will help you identify groups in your community that could serve on the Steering Committee, as a participant in community discussions, and/or as a member of a workgroup assigned to implement the selected activities/strategies.

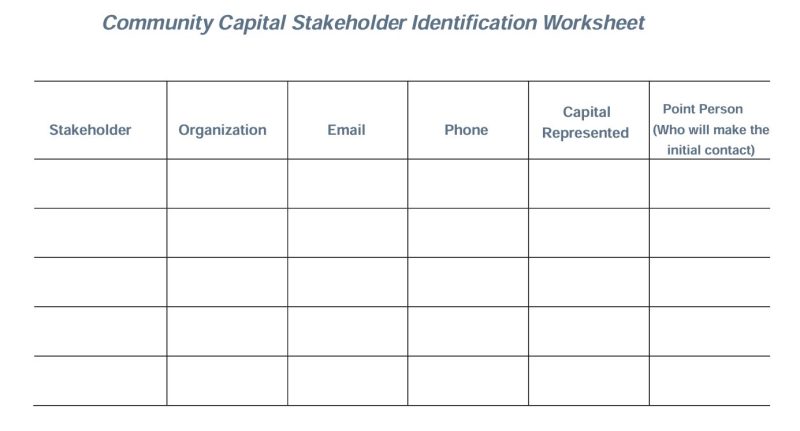

Use the Community Capital Stakeholder Identification Worksheet (Appendix B) and list people in your community who represent each capital. Collect the contact information for each named person if available and create a spreadsheet.

Within each capital include people from the various groups including the agricultural community, agricultural service providers, elected and appointed officials, community groups, the educational community, potential funders, gardening, local food groups, businesses, media, and interested individuals.

The recent emergence and increased demand for local food also provides an opportunity for urban and rural communities to connect around issues of health, food access and security, local economies, and ways to integrate good food from farm and urban homestead to table more effectively and efficiently.

- Personally invite those identified, clarify the issue being addressed, and explain the role they will play in leading this change process.

- Work with your original group to prepare an invitation.

- Ask each member of the original group to select a few of the proposed Steering Committee members to make a personal contact, discuss the issue, and the invite them to serve.

- Send a written invitation to each invited member once the initial contact has been made.

- Ask each invited member to respond to you (or a selected member of the original group) by a specific time.

- Communicate with the original group on the status of the Steering Committee.

- Express gratitude for each person’s service.

Steering Committee’s Purpose and Outcomes. Your steering committee may be assigned the following work:

- Gathering the facts on the current conditions of the CFS.

- Engaging a larger group of stakeholders in a discussion of the current condition and brainstorming possible improvements.

- Setting initial priorities for enhancing the CFS.

- Establishing work groups to review the priorities and build strategies that will create a positive change.

- Providing oversight to the implementation plans.

- Evaluating and reporting to the larger community on the change in CFS conditions.

Successful committee work is critical to the success of the program and requires a group of dedicated stakeholders who understand the issue, are motivated to invest in the work, and have the persistence to remain focused.

Some groups decide to modify the steering committee’s role thereby reducing work expectations and the time members are committed to serving. In a modified role, a steering committee would be established to host a community discussion, summarize the suggestions, and report on the findings. Once the report is delivered, the work of the steering committee would be completed and an implementation team would be established to develop the work groups, design the strategies, and implement the plans.

Whichever organization structure is selected, the group will function more effectively if the group has one person identified as the coordinator. This coordinator will need to apply leadership skills that build collaboration and engagement.

Step 3: Meet with the Steering Committee.

- Follow the best practices for effective meetings in scheduling and hosting the discussions.

- Develop and publish an agenda and record minutes of each meeting.

The first meeting (see Appendix C for possible questions) may have an agenda that includes:- Welcome & Introductions

- Express appreciation for each person’s willingness to serve.

- Invite each person to introduce him/herself and share a vision for a community food system.

- The Community Issue that brings us here today

- Explain what a community food system is and its impact on local residents.

- Invite participants to engage in a Story Circle to share their stories and experiences on a given topic or theme. Story circles are often used to build community and examine differences in values, racial experience, class structure, and cultural disparities. The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture (https://usdac.us/storycircles) provides general principles for using Story Circles to initiate community dialogues. Additional guidelines and resources are available at Working Narratives (https://WorkingNarratives.org), Roadside Theater: Art in a Democracy (https://roadside.org/asset/story-circle-guidelines?unit=17), and Stories of Community Food Work in Appalachia: Opening Space for Storytelling and Learning (http://blogs.lt.vt.edu/niewolny/).

- Present the facts . . . what we know about our community food system.

- Our Purpose as Members of the Steering Committee

- Clarify the purpose of the Steering committee

- Define why each person was invited to join the Steering Committee

- Confirm the Mission of Steering Committee and Role of Members

- Provide time for participants to discuss (perhaps in small groups) the purpose of the steering committee and the proposed role of its members.

- Gather edits and revisions to the wording.

- Reach consensus on both the purpose and member role.

- Develop Community Dialogue Plans

- Explain the purpose of the community meeting.

- Gather suggestions from the group on where and when a community dialogue on the local food system might be held.

- Create a listing of invitees.

- Prepare a listing of tasks required for a successful community discussion.

- Assign tasks to willing volunteers who will implement the Community Dialogue plans.

- Next Steps

- Review actions, who is responsible for the action, and the timeline.

- Schedule the next meeting.

- Always follow up with Steering Committee members prior to the next meeting by sending the meeting summary and a listing of assigned tasks.

- Remember, it is important to remind members of the next meeting at least 10 days prior to the meeting date.

- Welcome & Introductions

Whether you secure an external facilitator, you accept this role or a member of your group serves as the facilitator, you are tasked with engaging the participants in meaningful conversations, encouraging each group member’s personal investment and commitment to the work, and delivering support to the full group through inclusive communication and organizational practices.

Do you need a facilitator?

As one of the group’s organizers, you realize that there will be robust discussions on the topic of food, and you are wondering if you can manage the discussion by yourself. This is the point where you assess whether or not a facilitator would be beneficial.

Facilitators wil l act as a neutral guide, take an active role in managing the group’s process and h elp the group increase its effectiveness by improving its discussion practices and group structure.

The facilitator will build a neutral process that focuses on:

- What ne eds to be accomplished

- Who needs to be involved

- Design, flow and sequence of tasks

- Communication patterns, effectiveness and completeness

- Appropriate levels of participation and the use of resources

- Group energy, momentum and capability

- The physica l and psychological environment

Individuals involved directly with an organization may not be the best choice for your group’s facilitator because they are usually more accustomed to being a decision maker. An effective facilitator will stay true to the core values of valid information, free and informed choice, compassion, and internal commitment.

If you decide to use a facilitator to guide the group’s discussion and/or the community conversation, you will work with the facilitator to design a process that best matches the group’s culture and goals.

Source: Excerpted and adapted from Tom Justice and David Jamieson, The Complete Guide to Facilitation, (Amherst, MA: HRD Press, Inc., 1998 ©), p. 5. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, HRD Press, (800) 882-2801, www.hrdpress.com.

Drinkwater, Friedman, and Buck (2016) of Cornell University suggest that to find innovative solutions to complex issues a facilitator:

- Delegates responsibilities to all team members

- Prevents experts or personalities in certain fields from dominating meetings

- Encourages participation from everyone

- Keeps everyone focused on the agenda, problem, and strategy

- Promotes listening and mutual understanding

- Fosters inclusive solutions

- Works alongside and with people

- Understands the importance of follow-up and follow-through.

Drinkwater, L.E., Friedman, D., & Buck, L. (2016). Systems research for agriculture: Innovative solutions to complex challenges. SARE Handbook Series 13. Brentwood, MD: SARE Outreach Publications.

Step 4: Communicate with group members.

Community members expect to be informed; and as the group’s leader, it will be your task to communicate regularly with the group members. Remember,

- Every group discussion should be guided by an agenda or clearly defined discussion points. The agenda should be distributed to the group prior to the meeting date.

- Each discussion, whether it is a workgroup meeting or a meeting of the community, must be summarized and shared with all the participants.

You might use something as simple as a table where the dates, meeting type and an overview are captured.

Or you may find that more formal minutes are required.

Step 5: Gather relevant facts and trends related to Virginia’s food system.

Before the group launches the change process, you first must understand the current situation which requires an investigative look at data. Many groups gather as much information as they can locate and then become overwhelmed and unsure what all the reports and tables actually mean.

- Virginia Farm-to-Table Plan https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/CV/CV-3/CV-3.html offers an update of challenges facing Virginia’s food system

- Food Deserts in Virginia: Recommendations from the Food Desert Task Force http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/VCE/VCE-294/VCE-294_pdf.pdf

- Reports and food systems information https://ext.vt.edu/food-health/clrfs.html

- Examples of local community food system assessment https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/CV/cv-80/CV-81.pdf (Harrisonburg) or http://leapforlocalfood.org/leap/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Roanoke-Local-Food-Ag-Report_FINAL-1.pdf (Roanoke)

- The United States Department of Agriculture’s publication The Economics of Local Food Systems which outlines the assessment process including identifying the questions that will guide your data collection. https://www.ams.usda.gov/publications/content/economics-local-food-systems-toolkit-guide-community-discussions-assessments

- The Food Policy Networks (FPN) is a project of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future (CLF) and offers an array of resources available at http://www.foodpolicynetworks.org/food-policy-resources/

- USDA - Agricultural Marketing Service’s Local & Regional Food Sector resources and other USDA programs in the local food supply chain.

Summarize and share the relevant findings with the group as part of the meeting notes. During the data gathering process, the group may conduct a S.W.O.T. or S.O.A.R. analysis.

The SWOT.

A situational analysis that measures the internal strengths (S) and weaknesses (W) and the external opportunities (O) and threats (T) related to a given project, operation, organization, and/or community is affectionately known as a SWOT. Some groups have actually replaced “weaknesses” with the word “liabilities” changing the acronym to SLOT. However, the four categories are named, the intent is to gather perceptions, opinions, and facts on environmental conditions impacting the issue or entity being discussed.

SWOT Templates. The Community Toolbox offers an excellent overview of SWOT at http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/swot-analysis/main

The S.O.A.R. A strength-based analysis focused on the strengths (S), opportunities (O), aspirations (A), and results (R). This tool promotes a positive foundation for describing the issues surrounding the community food system. Available at https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/c.php?g=28374&p=4304702

Strengths: What can we build on?

- What are we most proud of as an organization?

- What makes us unique?

- what is our proudest achievement in the last year or two?

- How do we use our strengths to get results?

- How do our strengths fit with the realities of the marketplace?

- What do we do or provide that is world class for our customers, our industry, and other potential stakeholders?

Opportunities: What are our stakeholders asking for?

- How do we make sense of opportunities provided by the external forces and trends?

- What are the top three opportunities on which we should focus our efforts?

- How can we best meet the needs of our skateholders?

- Whoe are possible new customers?

- How can we distinctively differentiate ourselver from exisiting or potential competitors?

- What are possible new markets, products, services or processes?

- How can we reframe challenges to be seen as exciting opportunities?

- What new skills do we need to move forward?

Aspirations: What do we care deeply about?

- When we explore our valuses and aspirations, "what are we deeply passionate about?"

- Reflecting on our Strengths and Opportunities conversations, who are we, who should we become, and where should we go in the future?

- What is our most compelling aspiration?

- What strategic initiatives (projects, programs and processes) would support our aspiration?

Results: How do we know we are succeeding?

- Considering our Strengths, Opportunities, and Aspirations, what meaningful measures would indicate that we are on track to achieving our goals?

- What are 3 to 5 indicators that would create a scorecard that addresses a triple bottom line of profit, people, and planet?

- What resources are needed to implement vital projects?

- What are the best rewards to support those who achieve our goals?

The Key Assets. Identifying and building on a community’s key assets and resources is important for long-lasting social and economic development. During this discussion, the group will identify key assets and resources that will be needed to expand and strengthen the local food system. For example, participants might identify the following assets, resources, and opportunities:

- arable land

- equipment

- information

- proximity to markets

- farming expertise, skills, and labor

- supportive farm and food policies

- favorable community planning

- financial and service infrastructure

- a local identity and sense of place

- a spirit of civic engagement and community involvement

- youth development programs

- strong community advocates and active non-profit organizations

- supportive schools, universities, institutions, and buildings.

These assets, resources, and opportunities would easily fit within the Seven Community Capitals framework and categories, Emery and Flora (2006) define as follows:

- Natural (land, water resources, climate)

- Built (roads, buildings, infrastructure)

- Social/Cultural (people, communities)

- Political (governments, non‐profits, universities)

- Human (capacity‐ building, skills, science, research, development, planning)

- Financial (foundations, donors, access to loans or program funding)

- Cultural (local identify, a spirit of civic engagement)

Step 6: Understand the Theory of Change.

You have gathered the data and have defined the problem. Now the group is beginning to think about how to change these existing conditions and strengthen the local food system. Before you begin to launch yourself into a flurry of activities, let’s examine how a change in conditions happens.

The theory of change is a participatory process that leads to the development of long-term goals for changes in existing conditions. The process begins by identifying the problem and then reaching agreement on “what condition will result from the removal of the problem.” (Taplin & Clark, 2012, p. 3).

When the group defines the condition it wants to change, the next question that should be addressed is “what change in behaviors will create this change?” By identifying the behavioral changes, the group is now ready to outline the activities that will influence and change existing behaviors. Basically, a change in conditions is driven by a change in behavior and a change in behavior is driven by an adjustment in awareness, attitudes, aptitude, knowledge, and/or skills. This is the A B Cs of planning.

With the long-term changes stated, the work becomes a backward mapping process linking long-term outcomes, preconditions, and interventions. This pathway is the sequence in which outcomes must occur to reach the long-term goal.

Leadership, Transformational Change, and the Food System.

In a 1995 article on leadership and organizational change, John Kotter of the Harvard Business School outlined eight reasons why transformational efforts fail and what is needed to create and sustain change.

As different projects, programs and initiatives are developed to address needed change in the food system, Kotter’s outline continues to offer a solid framework and best practices for leading and encouraging change within organizations and the food system. He recommends:

- Establishing a sense of urgency;

- Forming a powerful guiding coalition;

- Creating a vibrant vision and picture of the future;

- Communicating the vision;

- Empowering others to act on the vision;

- Planning for and creating short-term wins;

- Consolidating improvements to produce still more change; and

- Institutionalizing new approaches so they become part of the culture and organizational behavior.

To encourage change and continue to be motivated, Kotter emphasizes that change is a process and not an event. Within this context, he also notes that maintaining the status quo may be more dangerous than pursuing the unknown (Kotter, 1995; Bendfeldt, 2012).

Developing a vision statement may be a difficult process. However, try to simplify the discussion by breaking the process into small steps conducted over several meetings:

- Ask the group, “If we do our work and achieve our goal, how would we describe our community food system?” “What would our preferred future look like?” “If this were perfect, what would it look like?”

- Capture the words and ask a small group of participants to draft a vision statement.

- Bring the statement to the full group for review. Ask the group, “What words do you like and want to keep, what words would you like to remove or add to clarify?”

- Refer the revisions to the work group.

- Invite the work group to bring the revised statement to the next meeting.

- Repeat the review and revision steps until consensus has been reached and the statement is adopted.

Vision For a Vibrant and Sustainable Regional Food System

Economic and social development

- builds health and wealth through regional networks

- increases capacity and connection for local residents

- is based on local vision framed by diverse community members

Farm-based business growth and development

- is sustainable with respect to profit and environment

- connects history, place, and community

- is based on collaboration, communication and commerce

Landscape

- maximizes diversity of crops and livestock

- utilizes perennial crops and polycultures

- realizes improvements to soil, water and air quality

- has riparian areas that provides wildlife and water quality benefits

The workforce

- is healthy, respected, well-trained, and paid fairly

- contributes to overall community

Processing, retail, and other food-related industries

- meet diverse value-added needs

- are geographically accessible and supported by federal/state policies

- provide assistance to connect food establishments with consumers, producers, and processors

Storage and distribution infrastructure

- are readily available, efficient, economical, and geographically and culturally accessible

- are flexible in handling diverse products and quantities

- are ecologically sound and owned within the region

Local government

- strengthens the regional food system by using economic development tools

- facilitates the expansion of local markets for local agricultural products

Education and research assistance

- encourages, supports and assists regional food value chains and networks

- disseminates needed information

- is provided by state universities, community colleges, and NGOs

Rural and city quality of life

- increase choices and opportunities

- increases ownership, empowerment, and relationships throughout the food system

- connects fresh, healthy, and local food to rural and urban citizens

Step 8: Explore and expose the options and select the focus.

Of all the things you do with your steering committee and community groups, the most fun process will be brainstorming the possibilities!

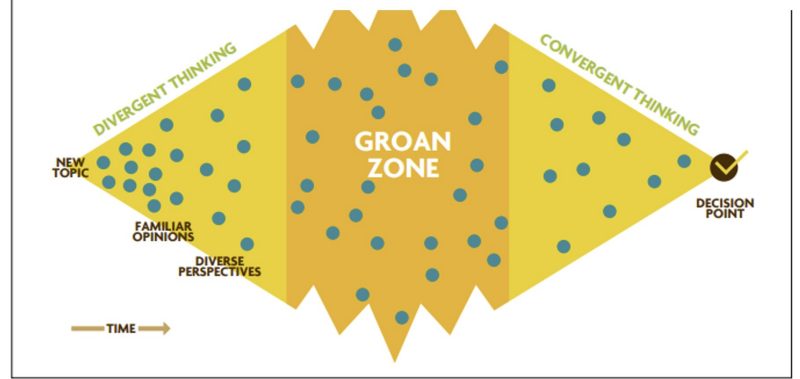

The brainstorming process engages all the participants in divergent thinking where each person is generating possible activities, projects, educational programs, mentorships, and hundreds of other ideas that address the identified issue.

The brainstorming process requires the use of appropriate facilitation tools and the support of an experienced facilitator. It begins with capturing the ideas and perspectives without judgment and using each idea as a catalyst for another thought.

With ideas generated, the process continues with the categorization of the array of thoughts into related groups. Once the ideas are categories, many groups enter what some facilitators refer to as the “groan zone!” Participants find it difficult to analyze the feasibility and potential impact on the issue. They may love the brainstorming but are extremely burdened with vetting the best solutions, prioritizing the actions, and building a plan.

In many cases, decision-making and the prioritization processes are based on the group’s shared core values, its human capacity to implement, and/or its financial resources. The process requires time, extensive conversations, data on the options, field trips, and any other engagement tools that will assist the participants in thoroughly vetting the options.

Step 9: Build a community food system strategic plan.

Your group has met for weeks building partnerships and relationships, examining the data, building its vision, exploring its assets and challenges, and setting its focus. Throughout the process, conversation notes were generated and communicated to the group. Because the group knew it wanted to publish a community food system plan and share it with the public, the text from the meeting notes, data on the local food system, the S.W.O.T. analysis, and the identified focus areas have been captured and written into a format appropriate for a member of the general public or a potential funder to read.

The American Planning Association (APA) outlined the outcomes of sound community food system planning and suggested that a community food system plan should:

- Preserve existing and support new opportunities for local and regional urban and rural agriculture;

- Promote sustainable agriculture and food production practices;

- Support local and regional food value chains, networks, business clusters and infrastructure involved in the processing, packaging, and distribution of food;

- Facilitate community food security, or equitable physical and economic access to safe, nutritious, culturally appropriate, sustainably grown food at all times across a community, especially among vulnerable populations;

- Support and promote good nutrition and health, and;

- Facilitate the reduction of solid food-related waste and develop a reuse, recovery, recycling, and disposal system for food waste and related packaging.

Before your group finalizes its strategic plan, you will want to review plans generated by other communities and include preferred components. There are, however, some basic components that should be considered for your strategic plan. Basically, you will need:

- Title page. It will be well designed with graphics that represent your community.

- Table of Contents. A key to guiding your reader through the document.

- Executive summary. The last item to be written and, perhaps, the most important because it may be the only page anyone actually reads. Provide an overview of the issue and define the focus areas for change. Keep the text positive and filled with confidence that the change will occur.

- History of the Local Food System. Outline the history of the community’s focus on the local food system. Include the origin along with the mission/purpose of the local food system advisory committee and community discussion groups.

- Mission Statement. Define the purpose of the organization and/or the work the group has been charged with completing. The statement is normally brief but may support the parameters outlined when the group was established.

- Value Statements. Describe the community’s core values related to food and its components and the importance of these values when building a flourishing food system.

- Vision Statement. Include the inspiring vision statement that builds a sense of place and local identity for what the local food system is when all the barriers are removed.

- Assets and Challenges. Summarize the facts and comments gathered through the data collection process and during the community S.W.O.T. or S.O.A.R. process. Use charts and graphics to provide a clear picture of the current conditions and available resources.

- Focus Areas. Explain what conditions the group wants to change and how work on these focus areas will impact the community. Include information on what indicators will be measured and how progress will be reported. Write a justification statement on why the investment of the community’s resources is important.

- Summary statement. Transition the reader from the strategic plan to the Plan of Work where the timelines and accountability measures are published. The summary sets the stage for future partnerships, funding, and organizational success by championing the organizational capacity to achieve its goals and carry out its mission.

Step 10: Write the plan of work.

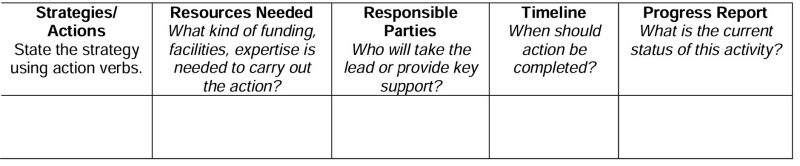

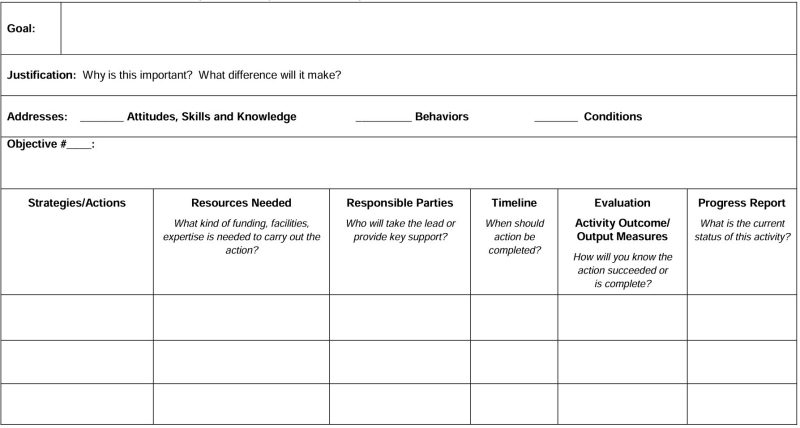

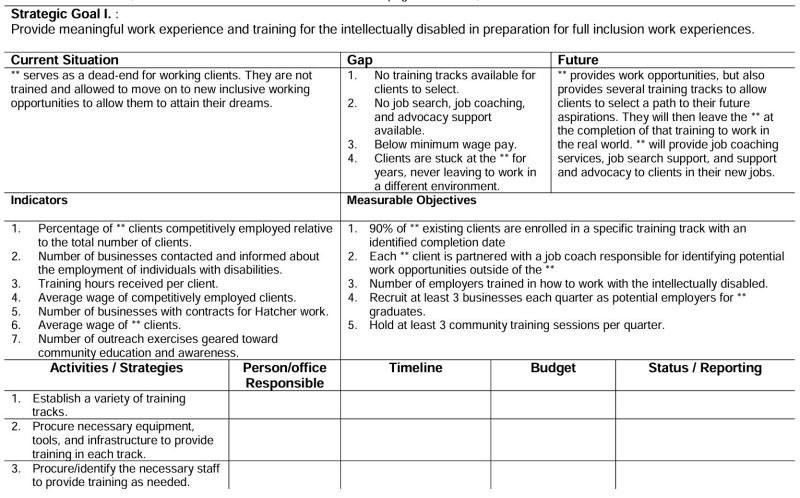

The public document is written but the work is just beginning. Each focus area selected by the group requires a detailed plan of work where strategies, actions, and/or activities are captured along with timelines, accountability, measurements, and reporting processes.

How is the plan of work developed? Once the most preferred ideas or solutions are selected, the work begins on the action plan (Appendix D). The plan provides a structure to effectively and efficiently track the work. It is usually a separate document for internal use only and:

- States the goals that are based on the group’s mission/purpose, vision, and values.

- Defines the goal as short-term (attitudes, awareness, and/or skills) or long-term (behaviors and/or conditions).

- Lists the action steps necessary to accomplish the goal.

- Identifies who will do which action step and by when.

- Includes a form of accountability by establishing measurements or indicators of progress.

Before the group begins writing, discuss the process for building the plan of work by asking a few key questions:

- What are the action steps for each focus area?

- Who will contribute to this work?

- How will we manage this work? What is our implementation structure?

- What are the indicators we will track and how do we measure our impact?

- How do we report on our work? Who receives the news?

- What data are needed for our reports? Who will collect the information? How will it be presented to the stakeholders/public?

- How do we communicate with our implementation team, the stakeholders, and the public?

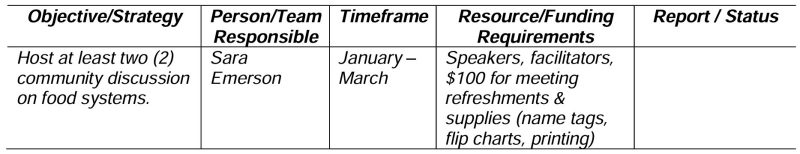

This conversation must be captured in a format that is easily managed. Many groups select a table format that can be updated monthly during the group’s reporting meetings. It might contain all the elements of a traditional plan of work (see Example 1) or be a modified version that fits the group’s needs (see Example 2). Whatever format is selected, remember to use action verbs and realistic timelines.

Example 1

Goal I:

Objective #____:

Justification: Why is this important?

Activity Outcome/ Output Measures

How will you know the action succeeded or is complete? (How will this goal/objective be measured?) By the number of programs, the number of participants, or some other measure. In most cases, you will want to know what impact the actions had . . . what difference the actions taken made.

Example 2

Focus Area Goal I: Expand access to locally grown/raised farm produce and products.

Justification: Why is this important?

Measurement: (how will this goal/objective be measured?) Number of programs, number of participants, or other measurement indicators. In most cases, you will want to know what impact the actions made . . . what difference did the actions that were taken make?

Reporting Outcomes and Measuring Impacts. At times, individuals and groups can be overwhelmed by the task of measuring impact and evaluating their work. An initial assessment of short-term outcomes might entail gauging general attendance and participation in programs and projects, but assessment of longer-term outcomes and impacts may be more involved and require different methods for gathering relevant data such as surveys, focus groups, one-on-one follow-up conversations, and ongoing research as well as relationship building.

Measurement indicators can serve as a proxy for shared values and overarching goals of the preferred future and vision you are working to create. From a sustainability perspective, assessment and measurement are usually in the context of social, economic, and environmental domains. Shared values on community food system programming may include engaging youth in gardening and introductory farming practices, providing education for producers and consumers, and making nutritious food affordable and accessible to everyone in the community.

In evaluating the overall sustainability of urban communities, Maclaren (1996) set the following criteria for consideration:

- Intergenerational equity: social changes between generations

- Intragenerational equity: social changes within a person's lifetime or the same generation.social equity, geographical equity, equity in governance

- Protection of the natural environment

- Minimal use of non-renewable resources

- Economic vitality and diversity

- Community self-reliance

- Individual well-being

- Satisfaction of basic human needs

For planning and evaluation, Abi-Nader et al. (2009) proposed a shared-value framework based on Whole Measures of Community-Based Food Systems, which included the following measures:

- Healthy People

- Food Security

- Sustainable Farmland and Natural Resources

- Agricultural Profitability

- Economic Development and Innovation

- Justice and Fairness

- Safe and Nutritious Food and Water

- Viable Communities

The steering committee and workgroup may also consider non-traditional out-of-the-box ways of measuring change. People’s stories and the experiences that they share can be extremely powerful in inspiring change and giving voice to impact. Therefore, be flexible and use indicators that fit the community’s context and needs.

Step 11: Moving Forward with Continued Networking

You have done all this work and delivered exceptional written documents. It is obvious this work will be a success. Well, maybe not.

Why may it fail? Over the years multiple groups have gathered at tables, discussed the conditions, brainstormed solutions, and prepared beautiful documents for public review. But, the groups did not stay true to the work. They lost their commitment, leadership was scattered, communication was absent, and the plans were soon lost on dusty bookshelves.

How it might succeed? Before your group meets the same fate, build an organizational structure within an existing system that will support the group’s work with logistical resources; provide technical support and leadership when needed; ensure accountability; and guide the evaluation, reporting, and revision processes.

Based on Methods for Community-based Participatory Research in Health (Israel et al., 2013) a successful community must build a foundation for its identity based on its assets, resources, and strengths. Equity, collaboration, power-sharing, and true equitable partnership will be highly valued. Successful communities recognize the importance of co-learning, capacity-building, and mutual respect and demonstrate concern for economic, social, and environmental health. Community leaders become systems thinkers in that change is dynamic, incremental, and requires continual feedback and improvement. Transparency and follow-up communication with partners and community organizations is a driving force and builds community-change processes that are relational and required long-term commitments to process and sustainability.

Core Capabilities of System Leaders: Individuals leading the community, local, and regional food system development efforts need the: 1) ability to see a larger system, 2) ability to foster reflection and generative conversations so people can “hear” a view different from their own, and 3) the capacity to shift the collective focus from reactive problem-solving to co-creating the future.

Kania and Kramer (2011) and Easterling (2012) outline tasks that networks need to strengthen their efforts to deliver systemic change and have a collective impact. Those tasks include:

- A common agenda and shared purpose across organizations;

- Gain and maintain credibility within the network and with the stakeholders/organizations critical to the network’s efforts;

- Keep focused on the core purpose;

- Identify and respond to the core issues;

- Develop strategies that are purposeful, practical and provide tangible results, and can be easily adapted to changing circumstances;

- Shared metrics and measurement systems;

- Mutually reinforcing activities that create synergy rather than duplication and redundancy;

- Continuous communication across and within departments and organizations;

- Engage a backbone support organization that can plan, manage, and support the initiative so it runs smoothly.

- Building and maintaining a diverse resource base that includes funders, businesses, universities, and the private and public sector; and

- Enhancing membership to increase effectiveness and the network’s overarching influence.

People and communities are ingenious and entrepreneurial. Similarly, community, local, and regional food system development is an extremely fluid and dynamic process. New opportunities and enterprises will continue to be explored and developed within urban and rural food and farming sector, but your educational efforts provide hope and promise for the present and future of your communities.

References & Resources:

Abi-Nader, J., Ayson, A., Harris, K., Herrera, H., Eddins, D., Habib, D., Hanna, J., Paterson, C., Sutton, K, & Villanueva, L. (2009). Whole Measures for Community Food Systems: Values-Based Planning and Evaluation. Fayston, VT: Center for Whole Communities.

Bendfeldt, E.S., Walker, M., Bunn, T., Martin, L., & Barrow, M. (2011). A Community-based Food System: Building Health, Wealth, Connection and Capacity as the Foundation of Our Economic Future. (Blacksburg, Virginia: Virginia Cooperative Extension May 2011. Retrieved from http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/3306/3306-9029/3306-9029-PDF.pdf

Bendfeldt, E. (2012). Leadership, transformational change, and the food system. Virginia Farm to Table blog. Retrieved from http://www.virginiafarmtotable.org

Campbell, M.C. (2004). Building a common table: The role of planning in community food systems. Journal of Planning Education & Research 23, 341-355, DOI: 10.1177/0739456X04264916

Easterling, D. (2012). Building the capacity of networks to achieve systems change. The Foundation Review, 4(2), 59 – 71.

Emery, M. & Flora, C.B. (2006). Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework. Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, 37, 19-35 (Spring).

Garrett, S. & Feenstra, G. (1999). Growing a Community Food System. Pullman, WA: Western Rural Development Center.

Goddeeris, L., Rybnicek, A., & Takai, K. (2015). Growing local food systems: A case study series on the role of local government. International City/County Management Association.

Hatfield, M. (2012). City food policy and programs: Lessons harvested from an emerging field. Retrieved from: http://www.portlandoregon.gov.bps/food

Hodgson, K. (2011). Planning for food access and community-based food systems: A national scan and evaluation of local comprehensive and sustainability plans. American Planning Association.

Israel, B.A., Eng, E., Schulz, A.J., and Parker, E.A. (2005). Methods for community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Kaner, J. (2014). Facilitator’s guide to participatory decision-making. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kania, J. & Kramer, M. (2010). Collective Impact. Stanford, CA: Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

Kotter, J.P. (1995), Leading change: Why transformational efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2), 59 – 67.

Maclaren, V. W. (1996). Urban sustainability reporting. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62 (2), 184-202.

Meter, K. (2011). Martinsville/Henry County Region (Virginia and North Carolina) Local Food and Farm Study. Crossroads Resource Center. Retrieved from http://www.crcworks.org.

Niewolny, K. (2013) Stories of community food work in Appalachia: Opening space for storytelling and learning. Accessed at: http://blogs.lt.vt.edu/niewolny

Niewolny, K., Latimer, J., Bendfeldt, E. S., Scott, K., Miller, C., Nartea, T., Vines, K., Grisso, R., Morton, S., Gerht, K., Githinji, L., & Tyler-Mackey, C. (2016). VCE Model of Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems (CLRFS) Forum Report (ALCE-154NP). Retrieved from http://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ALCE/ALCE-154/ALCE-154.html

Roadside Theater. (2014). “Story Circle Guidelines.” https://roadside.org. May 1, 2014. https://roadside.org/asset/story-circle-guidelines.

Senge, P., Hamilton, H., & Kania, J. (2015). The dawn of system leadership. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Winter/2015, 26 – 33.

Stavros, J. & Cole, M. (2013). SOARing towards positive transformation and change. Development Policy Review, 1(1), 10-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259975881_SOARing_towards_positive_transf ormation_and_change

Stavros, J., Cole, M. & Hitchcock, J. (2014, August). Appreciative inquiry research review & notes: A research review of SOAR. AI Practitioner, 16(3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284380692_Appreciative_Inquiry_Research_R eview_Notes_A_Research_Review_of_SOAR

Taplin, D.H. & Clark, H. (March 2012). Theory of change basics: A primer on theory of change.

New York: ActKnowledge. http://www.theoryofchange.org/wp- content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/ToCBasics.pdf

Taplin, D.H. & Rasic, M. (March 2012). Facilitator’s source book: Source book or facilitators leading theory of change development sessions. ActKnowledge. New York. http://www.theoryofchange.org/wp- content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/ToCFacilitatorSourcebook.pdf

The Community Toolbox. (n.d.) Analyzing problems and goals. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/analyzing- problems-and-goals

The Community Tool Box. (n.d.a). Coalition Building I: Starting a coalition. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/promotion-strategies/start-a- coaltion/main

The Community Tool Box. (n.d.b). Conducting effective meetings. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of- contents/leadership/group-facilitation/main

Tulane University. Tips for writing goals and objectives http://tulane.edu/publichealth/mchltp/upload/Tips-for-writing-goals-and-objectives.pdf

United States Department of Arts and Culture (2018). Story Circles: Tool for Community Dialogue. Accessed at https://usdac.us/storycircles

W.K. Kellogg Foundation. (January 2004). Logic model development guide. https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kellogg-foundation-logic- model-development-guide

Walker, M. (2008). Innovative Leadership: Building Community Connections. Virginia Cooperative Extension. http://www.cv.ext.vt.edu/topics/CivicLeadership/Innovative_Leadership/index.html

Walker, M. & Tyler-Mackey, C. (2012). Facilitation Series: Facilitating Group Discussions Generating & narrowing ideas and planning for implementation. VCE publication CV-7 http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/CV/CV-7/CV-7_pdf.pdf

Walker, M. & Tyler-Mackey, C. (2012). Facilitation Series: The Dynamics of Group Decision Making. VCE publication CV-8 http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/CV/CV-8/CV-8_pdf.pdf

Walker, M. & Tyler-Mackey, C. (2012). Facilitation Series: The things facilitators say facilitating groups.

Weinzweig, A. (2013). A lapsed Anarchist’s approach to managing ourselves. Ann Arbor: Zingerman’s Press.

Appendix A

The Seven Community Capitals

(Emery & Flora, 2006)

- Natural capital investments – Preserving, restoring, enhancing, and conserving environmental features in the community food system (CFS) effort.

- Cultural capital investments – Sharing cultural identities (heritage, history, ethnicity, etc.) to drive CFS effort.

- Human capital investments – Work expertise, education, or physical ability contributed to CFS effort.

- Social capital investments – Risks taken to express differences of opinion, organizations involved, involving youth, public participation/input, organizational link with nonlocal involvement, actions linking community to the outside, local and nonlocal organizations involved, organizational representative on decision- making board, number of different groups on board.

- Political capital investments – Political support, relationship presence, and nature of the relationship between CFS board and local, county, state, federal, tribal, and regional governments.

- Financial capital investments – Type of materials contributed to CFS effort, presence and sources of both local and external financial support, mechanisms used for leveraging financial support.

- Built capital investments – Infrastructure used for CFS efforts.

Building a Stakeholder Spreadsheet

Community Capital Stakeholder Identification Worksheet

Appendix C

Steering Committee & Community Discussion: Possible Discussion Questions

How would we describe our current food system?

What data are available on our community’s food system?

Who has the information?

What is in our community’s comprehensive plan? Are there ordinances that might limit or create barriers within a local food system?

What is our vision for our community’s food system? Example:

Where are the gaps between the current food system and our vision? What are our strengths and challenges/barriers?

How do we fill in the gaps?

What are the specific actions that we should take?

What are our top priorities for the next six (6) months?

What focus areas do we keep on the list to work on after our primary project is launched?

Some strategic directions might include:

- Producer and processor development, growth, and engagement

- Values-based food supply chain development

- Market and infrastructure development

- Business and enterprise development

- Aggregation of farmers/producers and farm products

- Logistics and distribution

- a. Address logistics and distribution opportunities at all scales and levels of a local and regional food system.

- b. Create critical links between production and the market.

- Access to land, labor, and capital

- Political and organizational education and outreach

- a. Educate key decision makers on the importance of food system work so it is part of political discourse and social investment.

- Shift cultural values and increase consumer demand

- Ongoing food system research and development

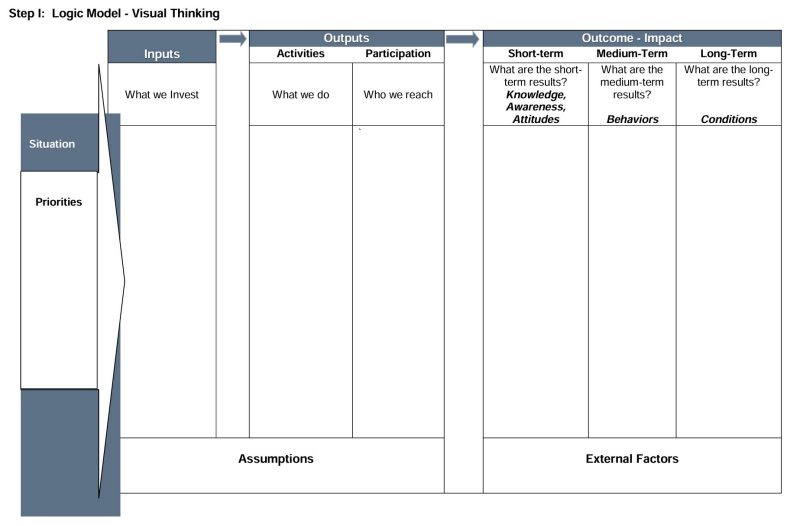

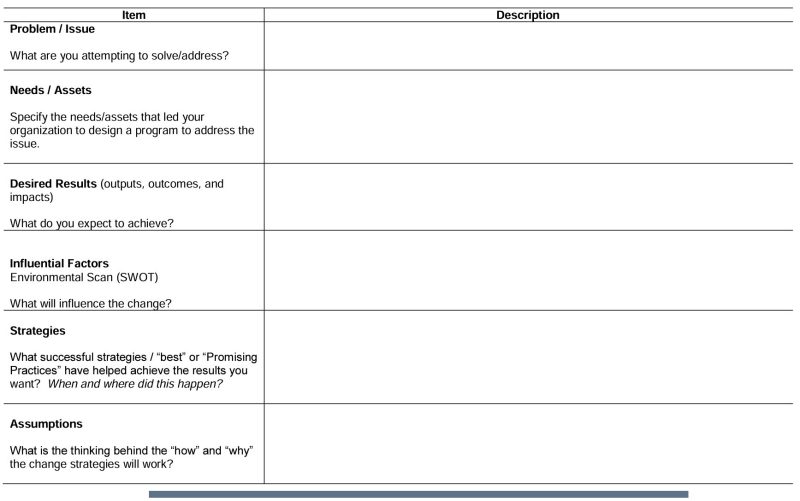

Step II: Program Planning Organization of Ideas (based on the W. K. Kellogg Foundation Guide)

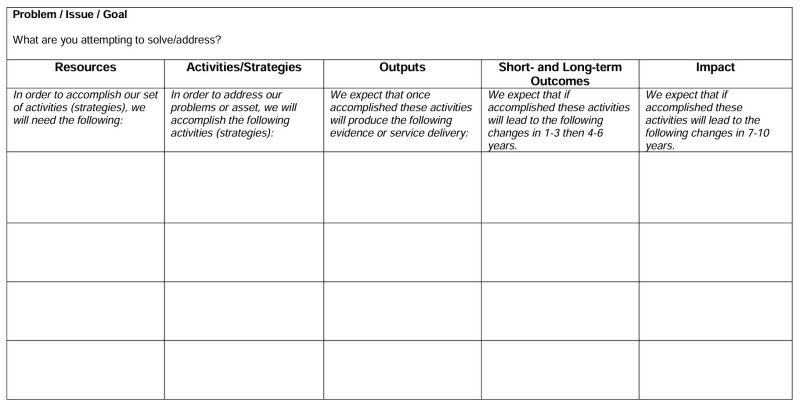

Step III: Implementation Resources by Issue / Goal Logic Model Development (based on the W. K. Kellogg Foundation Guide)

Step IV: Plan of Work for Planning, Evaluating, and Reporting

Action Plan

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

December 2, 2024